On the surface, learning history can seem like a tedious process of memorizing dates, names, statistics, and incredibly bland, one-sided narratives. At the ROM, they want to combat this trivial assumption of knowledge and foster a safe community where you learn that an object not only tells you what it is, but also what it isn't, why that matters, and what it says about you.

But how do you get to this kind of deeper learning?

Holocaust and Human Behaviour (Facing History)

Tagging along with the museum educators, I was able to take part in a two-day workshop on how to teach genocide to the public, focusing on school children and teens. Based on what I learned, here are three steps I think are necessary for teaching difficult history dealing with genocide:

1. Make the Learning Environment a Safe Space

We began our workshop by thinking about a moment where we felt our truest self and vice-versa. Collectively, using these experiences, we created a contract where we identified what was necessary to create a safe space for everyone. Key ideas like:

- Trust

- Open-mindedness

- Empathy

- Being non- judgemental

- Understanding your roles

These were the values we used to create a list of about 10 rules which would guide our discussion on genocide. Asking questions about genocide can cause anxiety and aversion unless the person is confident that their input, no matter how vulnerable they feel or how uninformed or loaded their input is, it’s ok to speak.

2. Avoid the Single Story

When examining an object, it is easy to say what you think it appears to be; however, it is easy to forget our perspectives are based on different cultural, locational, and unseen factors- also known as a bias.

It’s easy to say if you were in Nazi Germany you wouldn’t have become a Nazi. But what causes you to think like this? It's because you know what happened and aren’t surrounded by propaganda. Questioning knowledge and ideas is key to avoiding the "single story" or "one perspective".

Chimamanda Adichie’s video on “The Danger of a Single Story” goes further in depth into dealing with the “single story.”

3. Use Different Techniques to Create a Conversation

Everyone has different comfort levels when openly discussing a topic like genocide. By diversifying how conversations are held, you allow students who need more time to think and get comfortable to participate to the best of their abilities.

My favourite method was “Save the Last Word for Me,” where everyone breaks into smaller groups and everyone writes a question and an answer to their question. You would let the group discuss your question and after their time was up, you would “have the last word” and reveal your answer. This gently forces everyone to use their voice, giving everyone time to think.

“Save the Last Word for Me” and many more methods can be found at Facing History’s website:

https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies

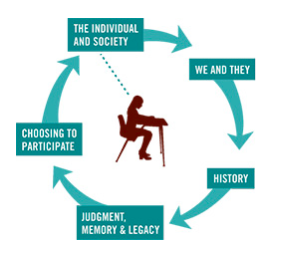

By allowing yourself and others a safe space to try work through the complications and delicacies of discussing genocide, it allows history to become a present, dynamic conversation; a conversation where you learn about the past through your own role in today's society.

Citations

1. “Save the Last Word for Me,” Facing History and Ourselves, Accessed October 15, 2018. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/save-....

2. Wong, Jasmine, “Workshop” (seminar, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ON, October 9-10, 2018).